Caldwell and Higgins: A Tale of Two Kevins

To be clear, I do not think biographical detail is a sufficient guide to interpreting an artist’s work. Nor do such details on their own define who or what a person is. Indeed, I do not think it is even the most important factor. But it does seem important nevertheless in this case. I have had two different name changes and published music under one name, and soon a book under another. Eventually, people will realize that a book written by Kevin Caldwell provides links to songs written by Kevin Higgins. Hence this bit of background about myself.

There are two threads with which I will weave this brief biographical section. One is the history behind my names, and the other is the history behind my soul. They are related stories, and so I will tell them together. I will try to focus on the most pertinent and explanatory facts.

I was born in Arcadia, California and given the name Kevin Lee Caldwell by my parents, Ralph, and Nelda. A few years later my mother left my father and moved in with her sister in Bakersfield, California. That is the town where I was raised, met the amazing person who has been my wife since June 18, 1980, and after many years away, returned and finished the process of releasing our three daughters into the wild world, whether it was ready for them or not.

My mother found a job in Bakersfield, finalized her divorce, met George “Mike” Higgins, fell in love, and remarried. They had a little boy of their own, named Michael. One of those life altering griefs left its shadow on all our souls when he died at the age of three during Easter week. Mike and Nelda tried to conceive again and after being unable to do so decided to adopt, which led to another life altering event, this being a beautiful one: the addition of my sister and brother to our family.

Meanwhile, my birth dad, Ralph, was very committed to staying in my life. He too had remarried, and had two more children, and thus I had another sister and brother in my life. As I grew older my visits with my birth father were becoming more and more difficult for me. That had nothing to do with my stepmother or my sister and brother. But I found myself more and more dreading the visits. I was also finding it harder to explain to my sister and brother in Bakersfield what all this was about: why they were not in touch with birth or foster parents, and why my name was different.

Everything about all this was awkward for me and I was too young to process it all. The only way I could see to handle it was to end the visits and be legally adopted and thus have a new name that matched the new family.

That is how I became Kevin Stuart Higgins, the name by which most people have known me since the middle 1970’s. It is the name to which my professional reputation, such as it has been, was attached. Which begins to lead me to the thread of the story of my soul.

I was a reluctantly obedient church goer for much of my youth but stopped when I could convince my mother not to force me. However, Christianity was not really a feature of our home life. I did come to realize that my mother was devout, but as my stepfather wanted nothing to do with any of it, our home life was largely a religious blank.

Around 1976 I began to search “spiritually.” I found Plato’s “Republic” on a shelf in the back bathroom and not knowing anything about anything, I started reading it. Intellectually, I did not grasp much of it at all. I was a senior in high school and my gray matter had no rungs on the ladder for me to climb along with Plato. But something was going on inside of me, nevertheless.

I was dating Susan, that wonderful woman I mentioned earlier to whom I am married all these years later. And together we took part in a small group discussion with others from the church about spiritual things. Pretty low key, very relational. And then in my first year of college I had what I can only describe as a “spiritual encounter” that was beyond words, was not reasoned into, was not a result of a process of logic, and which to this day I am not sure fully how to explain. It was in a Christian setting, and it involved what I describe as an encounter with God, the Spirit, Jesus, without any way of articulating then or now what all that meant.

The only path I knew for cultivating that new life, which is the word that seems to best describe it, was a Christian path. But it was an eclectic Christian path.

I was influenced by the charismatic movement which was then affecting mainline denominations and introducing many to what were for them, us, experiential realities of the spiritual life.

I was influenced by the contemplative streams of the Christian world too, and by 19 years of age I had met and begun a lifelong friendship with a man named Juan de la Cruz, John of the Cross.

Of course, he had been dead for several centuries when we met, and my soul was in no stage of development to fully receive the nutrition he had to offer. But as the years have passed, I have returned over and over to his wisdom, his words, his insight into the life of the spirit, and most recently, his profound insights into the possibilities for fullness of life as a result of the process of becoming more fully human, and thus in the Christian way of expressing things, more fully restored in and more fully reflective of the image of God.

John of the Cross describes that in words that could be re-expressed in way that suggests that the more fully human we become, the more fully we express what it means to be divine. Although he did not use those exact words, his thinking and more importantly, his life experience, was so close to what I am expressing here that he was subjected to the theological review and criticism of the official powers that be. He lived and wrote during the era of the Spanish Inquisition. And like many contemplatives in multiple religious heritages, his experience of God often outpaced that of his critics, and thus his words failed to find soil in their hearts in which to be appreciated.

I was also influenced by the evangelical heritage of the Christian religion. That is a stream which highly values experiential faith, has a long history of social activism (often held suspect by more modern evangelical adherents, sadly), and holds the scriptures in the Bible in high respect as the source and rule of faith and life and theology.

Finally, I was influenced by another stream that I will refer to here as “the arts.” I was a literature major for my undergraduate studies. I studied poetry, short stories, English and American literature, Medieval literature, Anglo-Saxon works, Greek mythology, Homer, etc. I wrote poetry. I did a few poetry readings. There was a sense in me in those early years that I was also meeting God in and through those works. I talked with artist friends as often as I could, some of whom were Christians. Some of them had similar experiences as I, some did not. I had no conceptual framework, at the time, to make sense of what I was experiencing or describe it. I just knew it.

There were more streams to come.

In 1980, in Glendale, California, I met and made friends with several Muslims. This began to stir in me a feeling I could not explain. I found I was very drawn to Muslims, and still am to this day. I wanted to learn more. Initially, that was inspired by the evangelical motivation of conversion, which I would have described as the traditional model of a conversion from one religion to another.

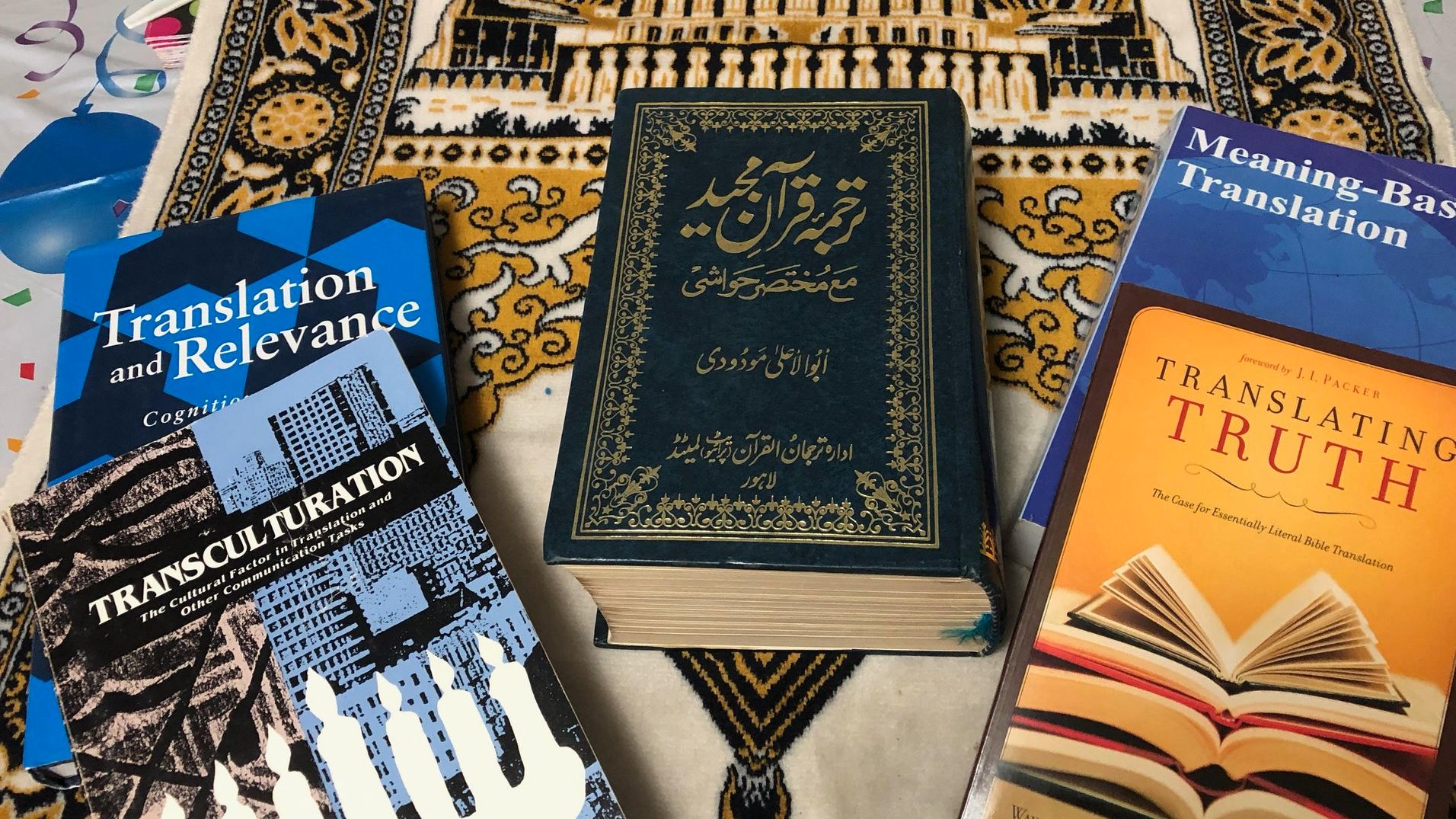

This set me on a trajectory towards living among Muslims. My first experience of that was a year in East Africa where I also purchased my first Qur’an and began to study it in Arabic with an Imam. I did so initially with an assumption that I would find “ammunition” for evangelism. Instead, I began to love the book. I did not have words for explaining this, nor did I feel comfortable telling many about it.

That aspect of my journey deepened in subsequent years when we moved to two different Muslim countries. We did so as missionaries. However, I was becoming more and more uneasy about the traditional model, the paradigm of it all, and the assumptions about cultures and religions and God that lay within the conventional paradigms.

I was discovering more in the Qur’an, yes, but also as I went back to the Jewish and Christian scriptures, I found I was reading them in new ways, or at least seeing things in them I had not seen before. I was re-evaluating my entire paradigm of religion, culture, and what is called conversion. To be clear, what was going on inside of me was not causing me to doubt the scriptures, but rather to see truths in them which the reigning paradigms did not account for. Indeed, those paradigms had kept me from seeing things in my own books, things always there, things which challenged much of what I thought I knew.

When we returned to the USA, for reasons I am not quite sure I can articulate other than by saying I was drawn to do so, I began to read the Bhagavad Gita, and Buddhist texts. I bought multiple versions of the Gita for example, including one with the Sanskrit text included, and began to dabble in trying to understand it more deeply.

I began to toy with the idea that if the Jewish and Christian concept of human nature is anything like the truth, if there is reality to humans reflecting God’s image, that is, if there is reality to the idea that humanity shows us what God is like, and if it is true that God created (without needing to define how), and that God is a Creative Being, then humans must somehow reflect that, we too are creative beings, and what we create is also part of how we reflect God’s nature.

The implication of that is that human beings are revelatory, and what we do is revelatory.

Thus, using a term Christians use for the Bible, it seemed to me that there is a canon of humanity: everything people do, create, and “are” is a set of texts that reveal.

I can hear the voices of some readers, because I have the same thought: not everything people do and create is actually good. Correct. Inescapably true. There is a mystery of human beauty, to be sure, but also a mystery of human tragedy and terror and cold and violent evil.

So, I began to think in terms of another concept that some Christians have employed: that there might be a canon within the canon. I won’t elaborate here except to say that it is not uncommon for Christians to interpret the Bible by elevating certain portions or texts over others, or to use the light of some texts to enlighten how to understand and apply (or set aside) others.

Muslims have approaches to this as well, and I have seen it in some commentaries on the Gita. In short, I have come to believe that within what I have called the canon of humanity there are other canons. I would describe it by saying there are people and texts and works which are “thin” places, so to speak, places where Reality is more transparent. How do we know which ones? I am more and more convinced that there are time tested texts and persons, tested over long periods, by many generations of people in many different contexts, and as a result these have been proven by experience to provide nutrients, sustenance, insight, wisdom, life. The fact that they do so for so many people in so many contexts over such long periods of time suggests there is something in these texts and people “bigger” than a culture or era or the individual themselves.

I began to develop what I now refer to as the concept of “mutualism” in the cultural and religious life of humanity. More than that later.

While all that was brewing, there were very few who knew about it. I tried sharing a few times with a few others and was met with mostly friendly but quizzical or even skeptical responses. I understood that. I still understand.

All the while as this soul story was unfolding, I was Kevin Higgins. I was leading a growing Christian mission organization, and while I was in some ways pushing some of the edges of Christian and evangelical mission assumptions, I was tentative about how much to say or share, and with whom.

Then a series of events took place in which the name Kevin Higgins was misused, and was attached by a few people to an anti-Islamic, pro-USA agenda, which was the opposite of my convictions and entire approach. It seemed clear to me that this connection could bring undue attention, even danger, to some of my friends in other countries. At the time, the advice we received, and which seemed wise to me then, was to change my legal name so that I would travel with that, but remain Kevin Higgins for my public life as a mission leader, author, etc.

Looking back, I can see many flaws in that approach. We all make the best decisions we can with the light we have at the time. As a result, I decided to change my legal name back to Kevin Lee Caldwell.

For years I have imagined different ways of addressing all this, of laying out my story. In 2017 I left my prior organization and worked in various leadership roles in another Christian and evangelical structure. My thinking kept evolving along the lines above, and eventually came to a head. My board and I reached a mutual decision that I would step down. While difficult in many ways, I began to sense that the time had come to lay out the story.

And so, I am Kevin Lee Caldwell, and I am Kevin Stuart Higgins. The histories of both are my history. The songs I began to record and publish in 2020 under the name Kevin Higgins are the songs of Kevin Caldwell. A book of poems and songs and essays about art which is near to being published as I write this, is Kevin Caldwell’s book. It is also Kevin Higgins’.

It is mine.

My journey from childhood to a multi-streamed Christian expression to my current “mutualist” approach to humanity and spirituality is the journey of both Kevin’s because I am both. My journey has led me here. It will lead me further.

Before concluding, it may be helpful for me to say a bit more about what I mean by mutualism. I plan to articulate that in much more depth in a book, but for now, let me begin from what I do not mean.

Mutualism is not merely tolerance. Tolerance is a good thing, don’t get me wrong. But it can be very detached. I can be tolerant easily when I don’t actually care about you, or about a topic, for example. “Do what you want, no skin off my nose.” That is not necessarily what tolerance means, of course, but it is possible to be tolerant for the simple reason that we just do not care.

Mutualism is not merely pluralism: pluralism, like tolerance, can be good. Pluralism in its religious application or cultural application is simply that idea that all the paths are fine, they all get to the same spot. Just as tolerance can be uncaring, so pluralism can be void of curiosity. Pluralism can be aloof and detached. “You do your thing, I’ll do mine.”

Both tolerance and pluralism can leave human beings detached and disconnected from each other, or attached and connected only to people who are like us, who already agree with us. People can end up living in very distinct compartments.

My concept of mutualism is different. I imagine a vibrant, open, receiving, giving, listening, speaking, humble, confident, gentle, courageous way of engaging with people and cultures and religions, and art, and life.

A mutualist approach, for example, to religion and to religious texts means that I can be fully confident in my heritage and texts and my love for them and appreciation of them, and I can bring that and share that and speak that. At the same time, I will want others to do the same. And for them to do so, I will humbly receive the same from others, not just to defend or argue or compare, nor to relinquish or acquiesce or make a false peace. Rather, I can receive, eager to learn, and be enriched, to see things in other heritages I never saw before. Then, because that will change me, it will also provide me with new lenses when I look back again to my own heritage. I will see things that have likely always been there, but hidden from my view because of the vantage point from which I was trying to look.

Mutualism will help me grow even in my own heritage, then. But it will also expand my sense of all that God as I understand God has done and is doing in the full scope of the world.

My journey has taken me in quite different currents from the several Christian streams I began to swim in originally. Even so, I retain to this day, albeit in redigested and reconstructed frameworks, elements from all the streams I have described. My Christian streams (evangelical, charismatic, contemplative), as well as the Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, artistic streams I have encountered. They all have contributed to the water in this river.

In the process of that journey of redigesting, Kevin Lee Caldwell has become less and less comfortable with several labels. I am not sure what to call myself, though I often use the phrase that I am a “Jesus Guy.” I am more and more frequently adding that I am a “Pre-Christian Jesus Guy”. Not because everything that developed in the later epochs of Christian history is wrong or to be rejected (though there is much that should be), but because there is always value in returning to whatever original spark gave birth to a religious or cultural or artistic movement.

Indeed, that is crucial for any renewal, to return to the spark. This is a topic that will need a lot more ink to explain. However, I will plan to revisit all this in the future.

Now you know a bit more of who the author is: Kevin Caldwell, who used to be Kevin Higgins.